As a vigneron in Burgundy, France, working in some of the world’s most legendary vineyards, François Morissette never imagined that one day he would return to Canada.

Then he was offered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity at a promising plot of land – gravelly, sandy loam soils – in Ontario. The winery wasn’t yet formed. It didn’t even have a name. However, the land, a beautifully-situated property in the province’s famous Niagara Peninsula region, was excellent. If he accepted the partnership, Morissette would have full control over what he made and how he made it.

“The offer was very enticing, very interesting,” said Morissette. “As a winemaker, I could do whatever I wanted.”

That’s pretty much all it took to strike a deal, and the winery was born. Located in the heart of Ontario wine country, near Jordan Station on the Niagara Peninsula, Pearl Morissette opened its doors in 2007.

Morissette has a collection of 30-some old foudres from Alsace; massive wooden vats that hold thousands of litres, some of which are as many as 80 years old.

The winery boasts a cellar and production facilities, a bakehouse and a multiple-award-winning restaurant on site. Canada’s 100 Best named the restaurant in Canada’s 100 Best in 2023 and 2022, and in 2019, it was named Canada’s Best New Restaurant by enRoute magazine.

The wines are for sale in select markets across Canada, including Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and, further afield, in Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and several U.S. states, including New York.

The idea behind Pearl Morissette started in the early 2000s, when news broke that globally-renowned, Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry would be designing a winery in Niagara. Anticipating the potential of being close to such a landmark, Toronto property developer Mel Pearl decided to buy the land next to the Gehry project.

The Gehry building fell through, but since he now owned a vineyard, Pearl decided to create his own winery. He began searching for a winemaker and Morissette’s name came up.

Born and raised in Quebec, Morissette headed to Europe when he was 19 and didn’t come back to Canada for five years. Backpacking his way across Europe, he picked olives, worked with donkeys and then fell into the wine industry in France, almost by accident, spending a year at Domaine Alain Gras in Saint-Romain, a commune in Burgundy’s Côte de Beaune.

Wine quickly became his passion. He returned to Canada and studied at École Hôtelière des Laurentides in Saint-Adèle, north of Montreal. He became a sommelier and worked at Laloux in Montreal and at Langdon Hall in Ontario.

However, the call of the vineyard was still strong, and in 2000, he moved back to France, working for top producers in the Cote d’Or including Frédéric Mugnier at Domaine Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier in Chambolle-Musigny, Christian Gouges of Domaine Henri Gouges in Nuits-Saint-Georges and Domaine Roulot in Meursault.

When Pearl approached him to talk about moving back to Canada, Morissette wasn’t convinced. At least, at first. “I was working with some of the world’s greatest red wine-producing soils,” he said. “And it’s very romantic, being in Burgundy.” However, he said, “There are also a lot of rules in Burgundy, a lot of hierarchy, a lot of limits.”

Ontario may have rules, but they aren’t quite as restrictive. A deal was made, and the winery’s name became a combination of their last names: Pearl and Morissette. There are about eight full-time staff on the winery team and about 60 staff in total, including seasonal workers.

“All winemaking comes from peasantry, and to be a peasant is to be in touch with what’s around you, to be as close as possible to the grapes in the field. Our wines are different because every single one carries this liveliness, this spirit. That is why we drink wine, right? Otherwise, we’d just drink grape juice.”

Francois Morissette, Pearl Morissette

With roughly 40 hectares of land, Pearl Morissette grows a variety of organic grapes, including Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Gamay, Riesling and Cabernet Franc.

They make both single varietal wines and blends. The 2020 Furie, for instance, is a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc, fermented with indigenous yeast in large concrete tanks and oak vats, then bottled unfiltered and unfined. The 2020 Irreverence is a white blend of Chardonnay, Viognier, Pinot Noir and Riesling. The team’s first Meritage, a blend of Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, harvested in 2019, is available now.

From the get-go, Morissette’s vision has been about following ancient winemaking techniques and sustainable practices.

“All winemaking comes from peasantry, and to be a peasant is to be in touch with what’s around you, to be as close as possible to the grapes in the field,” he said. “Our wines are different because every single one carries this liveliness, this spirit. That is why we drink wine, right? Otherwise, we’d just drink grape juice.”

While he believes in minimal intervention, he has limits. “It still takes some intervention to make good wine. If you leave it entirely on its own, you’re going to make vinegar,” he said. “You do need to understand how microbial life works and to be observant to what’s around you.”

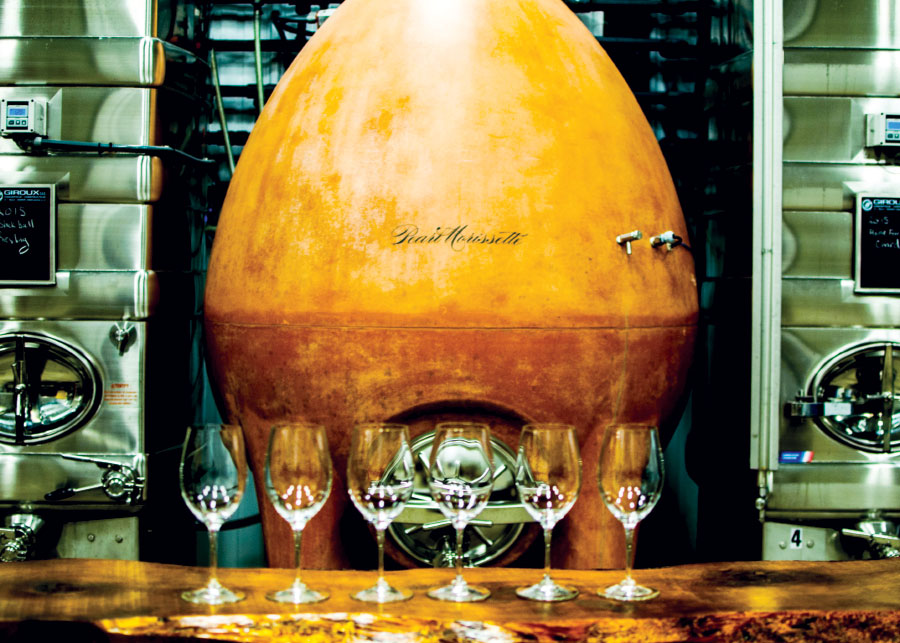

One of the first vignerons in North America to use concrete eggs for fermentation, he also uses Qvevri, terracotta clay vessels first used in the Republic of Georgia thousands of years ago. Morissette has co-fermented Gewurztraminer and Riesling in Qvevri for six months, with excellent results.

Morissette has a collection of 30-some old foudres from Alsace; massive wooden vats that hold thousands of litres, some of which are as many as 80 years old. “They are like casseroles. If you cook the exact same food in different pots and pans, you’ll have slightly different results, but they aren’t going to make the food,” he said.

That’s what it’s like using the foudres. They are too old to impart much, if any, oak, into the wines anymore, but they are an important tool for what Morissette wants to achieve. “They don’t make the wine,” he said. “But they help me focus my vision.”

Within the first vintage, the team had the attention of sommeliers, media and wine lovers across Canada for their complex and unusual wines.

“His wines are both idiosyncratic and remarkable,” wrote wine critic Eric Asimov in The New York Times in 2018. “His Chardonnays tend to be rich rather than lean, while the Cabernet Francs are pure, structured and lovely. His Rieslings are bone dry and age-worthy.”

All praise aside, Morissette is quick to clarify that he doesn’t have a favourite blend or varietal. “I always compare it to my kids. What kid do I prefer? I can’t say,” he said. “But some of the vintages I am most proud of are the ones that are most difficult to make.”

Take 2021, for instance. The extremely challenging vintage was marked by a harsher-than-usual winter, even by Canadian standards, with atypical temperature swings, heavy rain and unseasonable heat.

In response, the Pearl Morissette 2021 Chamboule Pinot Noir was fermented whole cluster in concrete and foudre, and the Oxyde Riesling entered the press as whole bunches. Relying on indigenous yeast, it fermented in concrete and foudres without temperature control or sulpher, and was then bottled unfiltered and unfined.

“I stuck to my narrative: very low intervention, only sulphur, and as little as possible,” Morissette said. “I was taking a huge amount of risk. It felt like I had a gun to my head, but it worked out.

“They maybe aren’t the most complex and ageable wines, but they took everything out of me. I discovered abilities I didn’t know I had, and I was lucky: It worked out.”